At 12, Drew McElroy was in trucking. His parents ran a freight brokerage operation out of a spare bedroom in Milltown, New Jersey—connecting truck owners to companies that needed to move goods—and he helped out by working the phones.

Fifteen years later, a light bulb went off. Weren’t truck brokers doing the same thing that Uber and Lyft do? They match rides to vehicles, minimizing wasted miles, and use algorithms to set prices based on supply and demand. “I realized, Holy crap, no one is doing this,” McElroy says. “There is a clear path to changing this entire industry that isn’t that complicated.”

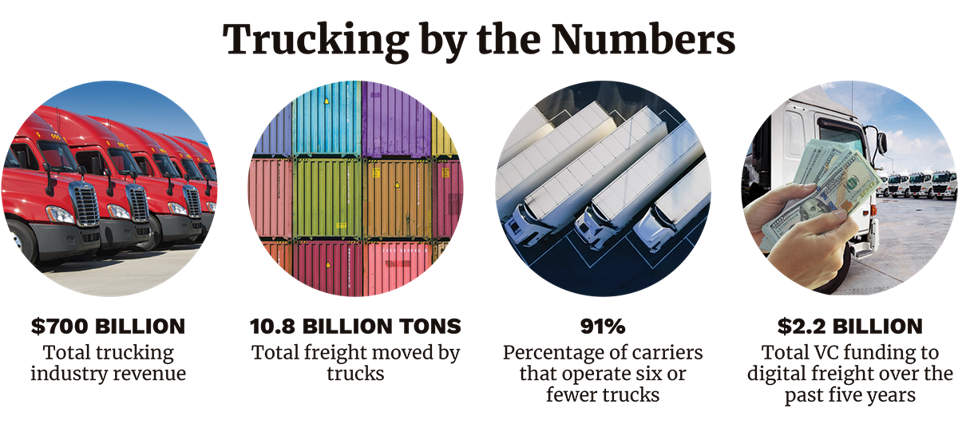

It was a smart idea. Trucking is a $700 billion market, and the bill for moving full truckloads in the U.S. runs to more than $500 billion a year. In 2013, four years after that aha moment, McElroy cofounded Transfix, an online freight marketplace that uses algorithms and machine learning to give full-load shippers better prices and truck owners better routes. The timing was good. Truckers, largely middle-aged men, had recently begun carrying smartphones and were willing to install the Transfix app.

Some shippers—companies that need to move stuff—have their own fleets of trucks driven by their employees. Walmart is one. But these are exceptions. Most trucking is done by contractors, and the vast majority of that by small operators who are desperate to keep their rigs full to cover the financing on those trucks.

Sources: American Trucking Associations, Pitchbook.

PHOTOS: GETTY IMAGES

Transfix, based in New York City’s Garment District, is on track to collect $100 million in shipping charges for 2018. It will remit the lion’s share of this gross revenue to people who own the vehicles.

With venture funding of $78 million from such firms as New Enterprise Associates and Canvas Ventures, the 140-employee business is worth roughly $800 million, gaining it a spot on Forbes’ 2018 list of Next Billion-Dollar Startups, one of two trucking companies to make the cut. McElroy, the company’s chief executive, and his cofounder, Jonathan Salama, its chief technology officer, have stakes that are probably worth $50 million each.

McElroy believes the company can reach $1 billion in revenue, with double-digit operating margins, by 2021, helping customers like Anheuser-Busch and Unilever manage their logistics while also enabling truckers to make more money by reducing the time they travel empty.

Since trucking was deregulated in the 1980s, some 18,000 freight brokerages have sprung up; the largest player, publicly traded C.H. Robinson, has less than 3% of the market. The potential for technology to streamline this work explains why digital freight brokerage is irresistible to venture capitalists.

Which means, of course, that Transfix faces competition, not just from Robinson but from newcomers like Convoy and Uber Freight. “This is one of the industries that venture loves,” says Ben Narasin, a venture partner at NEA, who personally invested in Transfix’s seed round. “I’m always surprised when I see any industry this big and antiquated.”

McElroy, a 36-year-old with auburn hair and bright blue eyes, was born in Paterson, New Jersey, where his father, Danny, who had served as a marine, was a dockworker on the midnight-to-8 a.m shift. The family struggled when McElroy was young, but his parents’ freight-brokerage business eventually became successful enough for them to send him to the Lawrenceville School, a prep school in New Jersey.

McElroy never quite fit in at the aristocratic institution and spent weekends hanging out with his childhood friends and drinking beer in the woods, but its academic rigor made Georgetown, from which he graduated in 2004, seem easy. “It is still today, even with Transfix, the hardest thing I have ever done,” he says.

McElroy returned to the family business after college. His dad was diagnosed with cancer in 2009 and died less than a year later. McElroy shelved his dream of an Uber-like startup long enough to help his mother get back on her feet—she’s still running the business—and then left.

McElroy took a 50-page business plan to San Francisco and slept on friends’ couches while he learned how to start a tech company. “I hustled,” he says. “It was my real-world M.B.A.” In 2013 a venture capitalist at Venrock who had also attended Georgetown introduced him to Salama, a Paris-bred consultant at the firm.

McElroy believes the company can reach $1 billion in revenue, with double-digit operating margins, by 2021.

Salama, now 32, had worked for Gilt, an online retailer, and Cherry, an on-demand car wash startup (subsequently acquired by Lyft). At Cherry he worked on building a marketplace that incorporated GPS tracking to match people who needed a car wash with those who would do the job. But his ideas for new companies went nowhere. “They were either good ideas but not in a big enough space or simply bad ideas,” he says with a laugh.

McElroy met Salama one evening in Brooklyn and pitched him on the idea for a digital freight brokerage. “It was like a great first date,” McElroy recalls. “I said, ‘Let’s talk in a couple of days.’ He was like, ‘You do all the thinking you want, I’m going home to start building the technology, and you tell me if I should ever stop.’ ” A week later they incorporated the business and split ownership 50-50.

McElroy updated his LinkedIn profile to say that he was chief executive of Transfix. The company was scarcely more than an idea, but within 30 minutes his cellphone rang. On the other end was Angelo Ventrone, then head of global logistics for Barnes & Noble. Ventrone, who is now vice president of logistics at the shipping-supply company Uline, says that as soon as they spoke he was ready to become Transfix’s first customer. “It was the dinosaur era for the longest time,” he says. “I said, ‘That solves a huge issue at Barnes & Noble. When can we start?’ ”

Transfix got a regular shipment of books from a printer in Indianapolis to a warehouse in New Jersey for $1,700 a load a few times a week, despite having no software in place. Salama was solving that problem, holed up in his apartment writing 10,000 lines of code. “Building things doesn’t come hard,” Salama says. “It takes a lot of patience and a lot of hours, but if you have a clear vision of the product, it just flows.”

McElroy raised $250,000 from friends and family. In January 2014, Salama finished the first version of the product.

To get rig owners to sign up, McElroy hung out at truck stops and went to the annual Truckers Jamboree at the Iowa 80 Truckstop. He offered drivers pork chops and beer if they’d download the Transfix app. One year the company set up a tank for a game of dunk-a-broker, a lighthearted way to make fun of the industry’s distrust of brokers. So far, 56,000 drivers have signed up.

The potential for technology to streamline this work explains why digital freight brokerage is irresistible to venture capitalists.

Historically, freight pricing has been both complex and opaque, which allowed brokers to squeeze smaller shippers and truckers and profit from a bigger spread. Transfix’s pricing algorithm, by contrast, spits out a rate without human bias, relying on information from thousands of data points, including historical shipments, loading times and weather forecasts. The company takes the risk that occasionally its rate will fall below breakeven and uses each new piece of data about cost to improve the pricing formula. Its matching formula, meanwhile, forecasts which truckers are most likely to want a shipment based on their current location, stated preferences and historical driving patterns.

Carriers need to make $1.70 per loaded mile to break even and lose money if their truckers drive empty, as they do for more than 50 billion miles a year. McElroy figures he can increase their take-home pay by routing them more efficiently. For shippers, the advantage is a better, more reliable price. Brokers earn money on the spread between what they make from shippers and what they pay truckers, typically around 16%; Transfix believes it ultimately may be able to use its technology to cut that spread in half.

“The beauty of this is it takes a lot of the cost out,” says Jay Pickett, transportation manager at Ravago Americas, the U.S. division of the Belgian plastics giant, which relies on Transfix for an increasing number of its 200,000 shipments a year. “I don’t think the big guys are ready to take that cost out and share it with shippers.”

Transfix’s real-time tracking allows shippers to better plan loading and unloading schedules, and occasionally catch fraud. In one instance, Transfix’s data indicated that a truck filled with aluminum ingots had gone off course; it ended up stopped at the side of the road in a bad neighborhood for hours, a red flag for a driver-enabled hijacking. More often, the data helps shippers prepare warehouses and workers for a truck’s arrival and let it pull up to door three, say, rather than door five.

McElroy’s expansion will be aimed first at international growth; later the company hopes to target shipments smaller than a full truckload. (The permutations and geometry of partial shipments will make that a challenge, even for Salama.) After a year spent focused on profitability, McElroy says, he can redirect his attention to growth. “I believe I am the luckiest man alive,” he says. “My mother would slap me if I ever lost sight of how lucky I am.”

This story appears in the December 31, 2018 issue of Forbes. View the original article here.

Leave A Comment